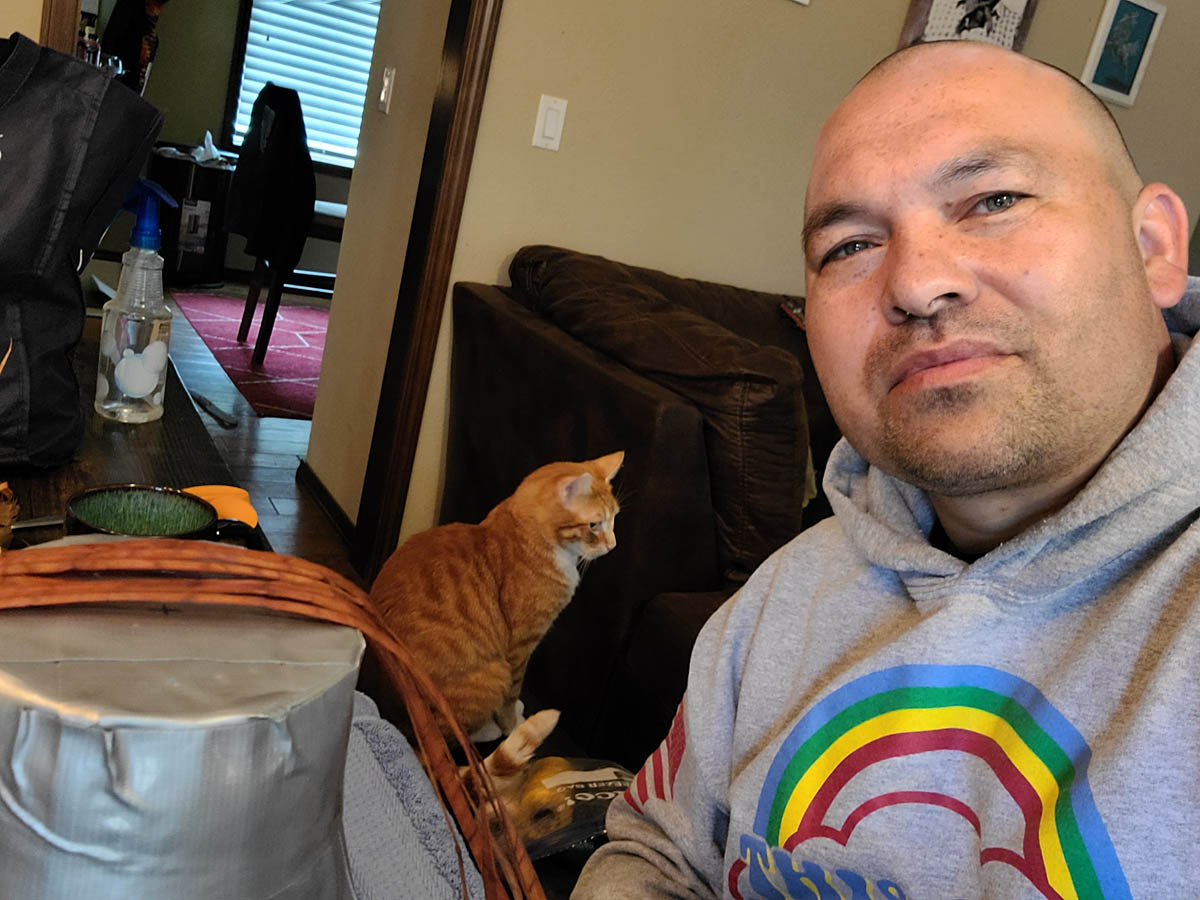

Indigenous Weaver, Ace Baker Sr.

Mt. Vernon, Washington

A Resiliency Fund Grantee Partner

It was during a Canoe Journey to Puyallup three years ago that Ace Baker Sr. first thought about making himself a cedar hat.

Baker and his family were camped in a spot away from where the main ceremonies were being held, and it was hot and dusty. He saw people walking around with cedar hats on, protecting them from the sun.

Fortunately, he and his family were traveling at the time with their friend Aurelia Bailey, the cultural events coordinator for the Swinomish Tribal Community. Baker asked her if she would teach him to make a hat.

“That knowledge was passed down to her—that line of knowledge goes back a long ways. And you know, she gave it to me freely,” he says.

Since the family was camped for two weeks, Baker had a bit of time on his hands.

“It took me a long time, because I have a real tedious brain. I was in the Army for 12 years, so I pay a lot of attention to detail. I took my time and I made my first hat—and it took me probably longer than it’s taken any other hat I’ve made since then—but I got it done,” he says.

Not that he got to wear it. “Just when I was about to finish it up, they said I was supposed to give it away—you’re supposed to give away your first project like that. So I ended up giving that hat to Aurelia. And I still haven’t made myself a hat,” Baker says.

Subsequent hats have gone to family and friends, and last year Baker donated one of his hats for the Potlatch Fund Annual Gala’s Silent Auction.

He attributes his affinity for weaving to his father. “He does a lot of beadwork and leather work, and he’s got his hands in everything. He’s a very artistic fellow, and so I get that from him,” he says.

Baker is a busy father of five sons who works as a fish and wildlife officer for the Swinomish Tribal Community. During the past couple of years, he was also getting his bachelor’s degree in environmental studies from the University of Washington, and he is now contemplating a return to school to get his master’s degree in education.

In some ways, being busy seems at odds with the time and patience required to make a cedar hat—and a process that can take months, start to finish.

Harvesting the cedar.

First there is the harvesting of the cedar, which starts with finding a tree big enough that you can’t get your arms all the way around it.

“You want the tree big enough to be able to survive any kind of trauma….and it’s got a straight area where you can chop and pull up and get a nice piece off…so you don’t want the part you’re harvesting to be bigger than the width of your palm,” Baker says.

Once you have the long cedar strips, the hard bark must be removed with a knife, and the strips rolled up and left to cure.

“So I just let mine sit in my garage for six to eight months, and then after that I can start processing it,” Baker says. Preparing the cedar requires soaking it for two to three days, and then sitting out on the porch using a leather stripper to “fetch” strips that will later be further split into strands for weaving.

Weaving, a metaphor for life.

For Baker, the actual process of weaving is a metaphor for life, of sorts. “It’s the most peaceful and beautiful thing that I think I do, really, as a stress reliever for me is to make a hat. It’s also very difficult.

“Sitting at this hat like this for three days….when I’m done with a hat, my back’s hurting, my arms are hurting, my shoulders are a little sore, my fingers will hurt, I’ll get callouses on my fingers, but it’s a process…a beautiful process, but as with all things in life, it’s beautiful and it’s painful,” he says.

It’s also a process that’s helped him cope with the past year and a half of COVID-19 lockdowns and uncertainty, which included being furloughed from his job for three months. “I’ve had a couple of tough years, you know, and whenever I got down and out, I started thinking about a hat, a design or certain things I want to do. It takes my mind off of the pain or whatever trials and tribulations I might be going through. And then, once I start working with it, that is medicine,” he says. “It helps me get through a lot.”

Passing on tradition.

Baker is from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, but his wife and sons are all enrolled members of the Swinomish Tribal Community, and Baker says he has been treated like family in the Swinomish community. Now, he wants to give back.

With a Resiliency Fund grant, Baker plans to produce an instructional video about the process of cedar hat weaving for the Swinomish community, all the way from harvesting the cedar to completing a hat. He sees modern technology as a valuable tool to preserve traditional ways for future generations.

“I am not asking for anything in return,” he says. “I am completely happy to know that the lessons that were given to me freely would be passed on to future generations in the same manner.”

Press Releases:

Pandemic reveals immense need – Potlatch Fund commits to raising additional $7 million for its Resiliency Fund

Native-Led Potlatch Fund Is Asking The Native Community To “Bring Us Your Dreams.”

More about the Resiliency Fund:

The Resiliency Fund Reveals an Immense and Enduring Need in Native Communities.

Potlatch Fund and the Future of Philanthropy

To Our Resiliency Fund Grantee Partners–Keep Sending Us Your Dreams

Announcing New Resiliency Fund

Stories from our Grantee Partners:

Indigenous Weaver, Ace Baker Sr.

The Young Warrior Society

Nimiipuu Nurtures Emerging Environmental Leaders

For Grantee Partners:

Resiliency Fund Application Information Here: Bring Us Your Dreams

If you are interested in supporting the Resiliency Fund: email us to discuss your giving or donate here to support the Resiliency Fund.