When he was growing up in Lapwai, Idaho, Rickey “Deekon” Jones remembers regularly leaving school

at the end of the day to head for the elders’ center on the Nez Perce Reservation where he lived. There,

he would hang out for hours while the women weaved and the men told stories and joked in the

Nimiipuu’s traditional language.

“It was a comfortable place for me to be,” Deekon says. “And outside of that, I managed to stay clear of

substance use, and I credit that a lot to the elders there. They would always tell me stories and tell me

how to act, how to carry myself and everything.”

Even as a young boy, though, Deekon was aware that many of his friends weren’t so fortunate.

“A lot of my friends experienced substances, and they were abusing substances and getting into a lot of

trouble, and they kind of pushed me to see what I could do to change this outcome. I always wanted to

find a way to help them and their families,” he says. “So I think that’s what pushed me, more than

anything, was growing up in that environment.”

Fast forward a few years, and Deekon was on only the second airplane ride of his life, headed to Eastern

Arizona College on a basketball scholarship. His time there lasted less than a year.

“It was culture shock more than anything,” he says. “They didn’t understand my brand of humor as

much. There wasn’t really community. Everybody was there for themselves, and I thought I’d be okay

with that, and then I just started feeling more and more out of place as time went on.”

In his tribe, he says, it’s common to “joke 24/7,” and having to explain himself left him feeling isolated.

“And I’m like, now I’m just sitting around here even more quiet than I already am, and not joking, and I

need to go home.”

He ended up enrolling at North Idaho College in Coeur D’Alene, Idaho, which was only a two-hour drive

from Lapwai, and there he found enough Indigenous students to feel like he had a community again. But

it wasn’t long before he left school and moved to Spokane. “I was finished with basketball,” he says. “I

didn’t love it anymore, and I didn’t know what I was going to do.”

In Spokane, he lived in his car for six months, parked outside a recording studio. “I had to see if there

was something else I loved,” he says.

He started showing up at the studio every day before most everyone else was there and spent his days

watching the audio engineer work and taking mental notes. “And then one day, he wasn’t available but

he had clients, and I just told them I could do it. And that’s what kind of got me off the street and into

building everything I have music related now,” he says.

A love of music is nurtured

Deekon knew he loved music. His love of music, he says, came from the Motown he used to listen to

with both his father and mother. “My dad had vinyl and eight tracks and my mom, she would always, no

matter what she did, have music playing and it was always Motown, and so every day my life was just

Motown. And so I’m a little kid singing all these Motown songs, and I’ve loved it ever since then.”

Eventually, he started writing his own songs at the studio. At the same time, there were people his own

age and younger coming to the studio to record, and he started writing and selling beats to them. “And

nine out of 10 times, it was something really sad, like minor key beats that were just really good for

storytelling because that’s what I like to do. And they were like whoa, that’s deep, you know, I’ll write

something to it.

“And when they come back, they would have to match the energy of the song, so the songs were really

deep. And I’m like man, I can really talk to these people about their lives through this music,” he says.

“It’s a lot easier than me striking up a conversation with somebody who’s had trauma in their life and

saying, ‘Tell me about your trauma.’ So in talking to artists who were writing to my set, I would be

finding out all these things about their lives.”

A program is born

On his own, he began researching the connection between trauma and the brain, trying to figure out the

correlation to music. He discovered that what he was doing was more along the lines of experiential therapy, as opposed to traditional music therapy. With this new realization, he returned to Lapwai and started working at the Boys and Girls Club. Supplied with just a computer and a microphone, he began a music program. The results were immediate and so powerful that they ended up shutting down the program because the staff members weren’t trained counselors.

Eventually, he got hired to monitor the patients at the Healing Lodge of the Seven Nations, an

adolescent residential chemical dependency treatment center in Spokane Valley, Wash. He suggested

trying his music program there with the patients. It took him a while to get permission. At the time, he

says there were a lot of kids getting kicked out for rules violations like running away or destroying

property. So he created a survey to ask the kids what they thought would help.

“And every single kid had music on their list in one form or another, and I brought that back to the

administration.”

Initially, he was allowed to take kids off-site to a studio to work, but the results were so promising that

he soon got the green light for a formal music program. The result was Healing Through Hip Hop,

although the program welcomed participants to choose their own musical genres. “We’ve done some

country, we’ve done a lot of rock, some spoken word poetry,” Deekon says.

With Deekon’s help, kids in the program wrote, produced, and recorded music, through which they often

revealed the traumas in their lives, a process that was then paired with dependency counseling and

experiential therapy.

Healing Through Hip Hop attracts national attention

The approach was so successful, it attracted considerable attention from the mainstream medical

establishment. In 2011, Healing Through Hip Hop won the “Innovative Program of the Year” from the

Washington State Department of Behavioral Health and Recovery. The next year, Deekon was a finalist

in President Obama’s Native Youth Challenge. In 2013, the program partnered with Harvard Medical

School’s Division on Addiction.

Recently, Deekon has been working with the University of Washington’s CoLab for Community and

Behavioral Health, which engages community expertise and research evidence to make changes in

behavioral health policy and systems. Through this partnership, he completed a training manual, and the

program is being evaluated to determine if it qualifies as an evidence-based practice.

“This program came from the Reservation,” Deekon says. “This program isn’t built on Western standards

of psychology, and now with working through this training manual and working with the CoLab, it will be

an evidence-based program that’s culturally competent.”

There is the hope that Healing Through Hip Hop will become a pilot program for how other community-based programs are evaluated and adopted. Along the way, Deekon says he’s had to fight for the program to be recognized by Western medicine as effective and worthy of funding, and he’s aware that many community-based programs haven’t been so lucky.

“It’s been so frustrating, and I’ve just kind of been so stubborn that I never gave up,”

He recently began a new venture, founding an organization called Community Development Initiative

with the mission of increasing neighborhood vitality throughout Spokane, where he lives part-time, by

serving BIPOC businesses and entrepreneurs with training and education, funding, and increased

visibility. He sees an opportunity to help individuals and programs succeed that are all-too-often ignored

by mainstream establishments, because they are BIPOC led and may not qualify for traditional loans and

funding streams.

“And you’re trying to come into a predominantly White space, and so I want to provide the space to be

able to fund those programs, give them space to operate and grow, just like I’ve struggled to do,” he

says. “I hope to be the one that goes through all that storm and makes it a little less turbulent for those

who come after me.”

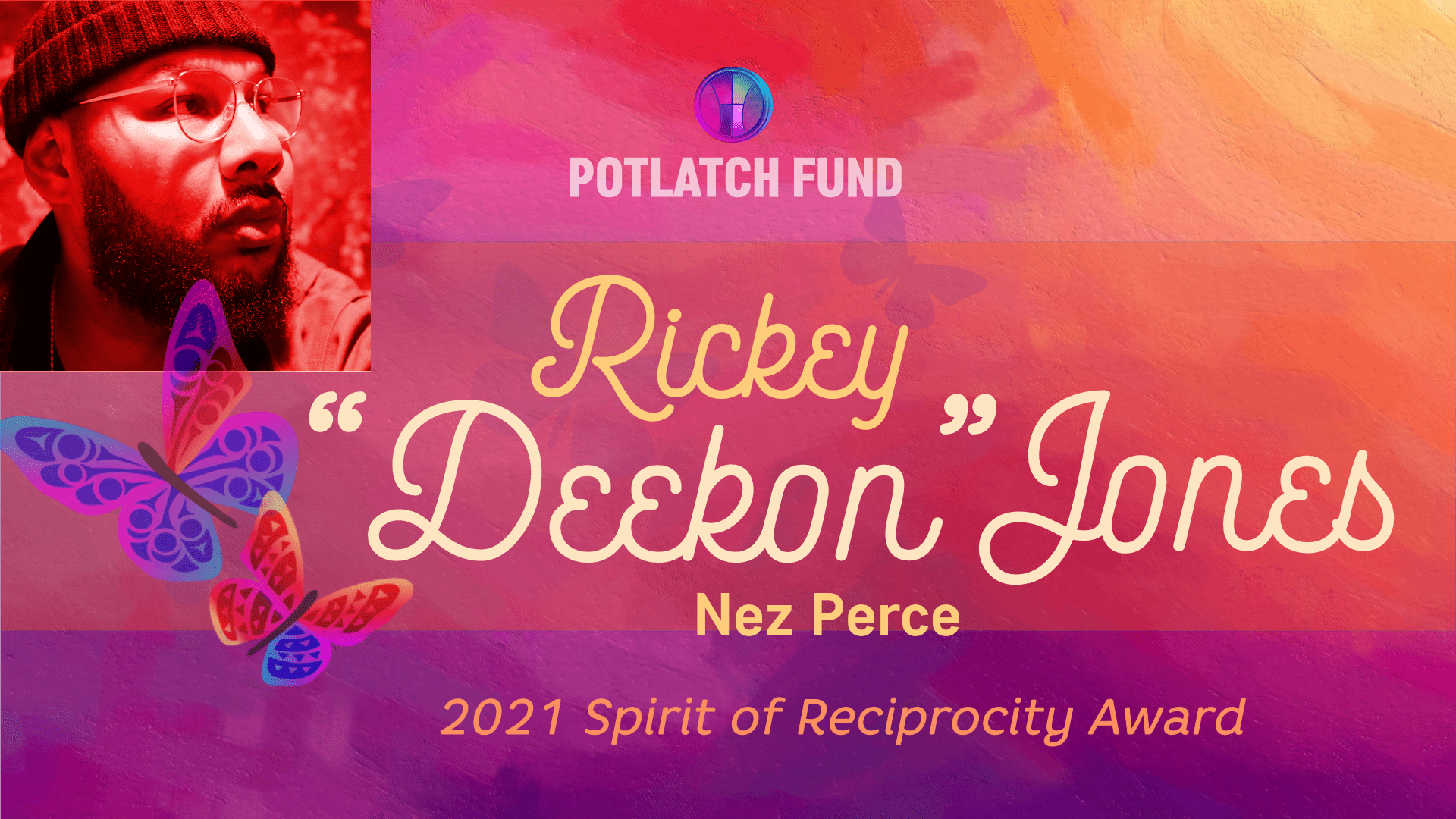

Join Potlatch Fund in congratulating Deekon as our 2021 Spirit of Reciprocity Awardee at the 19th Annual Fundraising Gala for a week of Giving & Gala Events celebrating Indigenous Vibrancy. Monday, November 1 – Saturday, November 6, 2021. Register and tune in to see Deekon’s award – Nov. 4th

Register HERE: https://bit.ly/19thAnnualGalaRegistration